If you ever need a reminder that snakes have a sense of drama, spend a breeding season watching a male python pursue a female twice his size. For all our talk about reptiles being “cold” or “simple,” nothing about their courtship behaviour is either of those things. And recently, inside the Indian Rock Python enclosure at Sardar Patel Zoological Park (Ekta Nagar, India), one male proved exactly that, using a pair of evolutionary leftovers—pelvic spurs—to turn mating into something of a full-body negotiation.

Pelvic spurs are tiny, claw-like structures sitting beside the cloaca. They look insignificant, but they’re fully equipped with their own nerves, muscles, and blood supply. They’re the last vestiges of the hind limbs ancient snakes once had. Most modern snakes have lost them entirely, but pythons and boas have kept these little relics, largely because they still matter—especially during courtship. In males, they’re larger and more mobile, nature’s way of leaving behind a specialised tool for moments exactly like the one that unfolded here.

SPZP keeps a small python group: one male and three females. As is typical of this species, the ladies are considerably larger. The biggest female crosses the 2.4-metre mark, while the male is about 1.55 metres. So the size imbalance already sets the stage for a story where persistence matters more than intimidation.

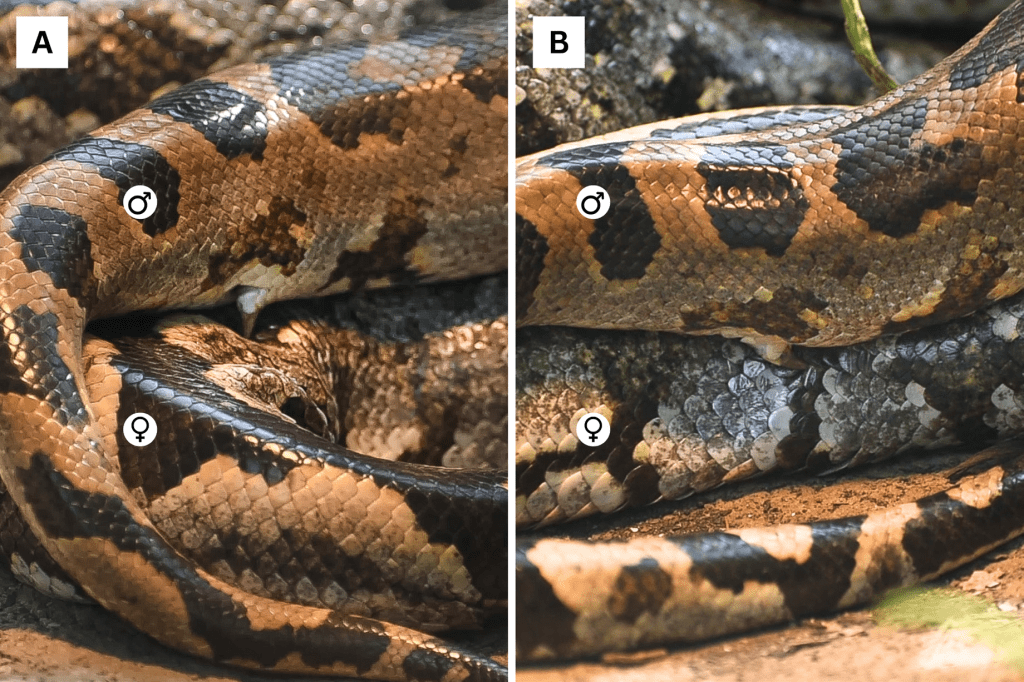

On 2 February 2024, the keepers noticed the male gliding toward one of the females with clear intent. What followed was not a gentle introduction. He went straight to work with his spurs—prodding, poking, and running them along her body with the confidence of someone who has rehearsed this choreography for millions of years.

He wasn’t fumbling. Everything was deliberate. Over the next few hours, he climbed over her back, aligned his body with hers, and travelled from tail to neck with carefully timed spur strokes.

At one point, the female slid into the thickest vegetation available—perhaps seeking privacy, or perhaps signalling that the poking had crossed from persuasive to mildly annoying. Either explanation fits perfectly.

The dance continued across several days, with its own highs and lows. On 8 February, he succeeded in stimulating the female enough that she remained still, allowing the courtship to progress smoothly. Later that week, another female expressed her disinterest with full clarity by vibrating her tail and body for nearly half an hour—an unmistakable python version of “No, thank you.”

What stands out is how the male used his spurs not only to stimulate but to position the female. With such a pronounced size difference, subtle body adjustments matter. The spurs help trigger tiny shifts in posture—some encouraged by sensation, some likely by mild discomfort—that make alignment possible. In other words, the male was using the last remnants of ancestral limbs to negotiate with a partner far bigger than himself. 🎵🎶Baby Got Back🎵🎶

It’s remarkable how behaviour carries evolutionary memory. These spurs have survived for millions of years because, quite simply, they still work. And for keepers and managers, understanding these details aren’t just interesting—it’s useful. It helps refine pairing decisions, interpret courtship signals, and recognise when behaviour is progressing normally or when something requires attention.

What looked like a simple sequence of nudges and rubs was actually a sophisticated communication system, sitting quietly between anatomy, instinct, and opportunity. Watching it unfold is a reminder that even species we think we know intimately still have layers of behaviour that surprise us.

And sometimes, all it takes is one determined male and two tiny pelvic spurs to show us how much there still is to learn.

Original Article

This blog article is adapted from the research note:

Trivedi, K., S. Prajapati , V. Kansara & S. Mukherjee(2024). Insights into the use of pelvic spur in mating behavior of Indian Rock Python. Reptile Rap #258,In: Zoo’s Print 39(8): 11–13.

Leave a comment